N4S: Rivers unite India, but politics keeps dividing them – and this article shows how. UPSC often frames water disputes as system-failure questions (like the 2013 mains on structural vs process flaws). Many just cite Cauvery or case laws, but miss deeper issues – no standing tribunal, murky data, Centre-state blame games – all unpacked under “Fundamental Structural Ambiguities” and “Challenges in Tribunal Functioning.” This piece fills that gap. It maps how tribunals crawl (“Process of Dispute Resolution”), why awards stall (Cauvery took 17 years), and how Article 262’s vagueness lets disputes return to the Supreme Court.

Bonus: it blends legal structure with lived realities-like Sutlej farmers in “Punjab-Haryana Water Dispute”-so you can fuse policy with people in your answers.

PYQ ANCHORING

GS 2: Constitutional mechanisms to resolve the inter-state water disputes have failed to address and solve the problems. Is the failure due to structural or process inadequacy or both? Discuss. [2013]

MICROTHEMES: Nature of Indian Federalism

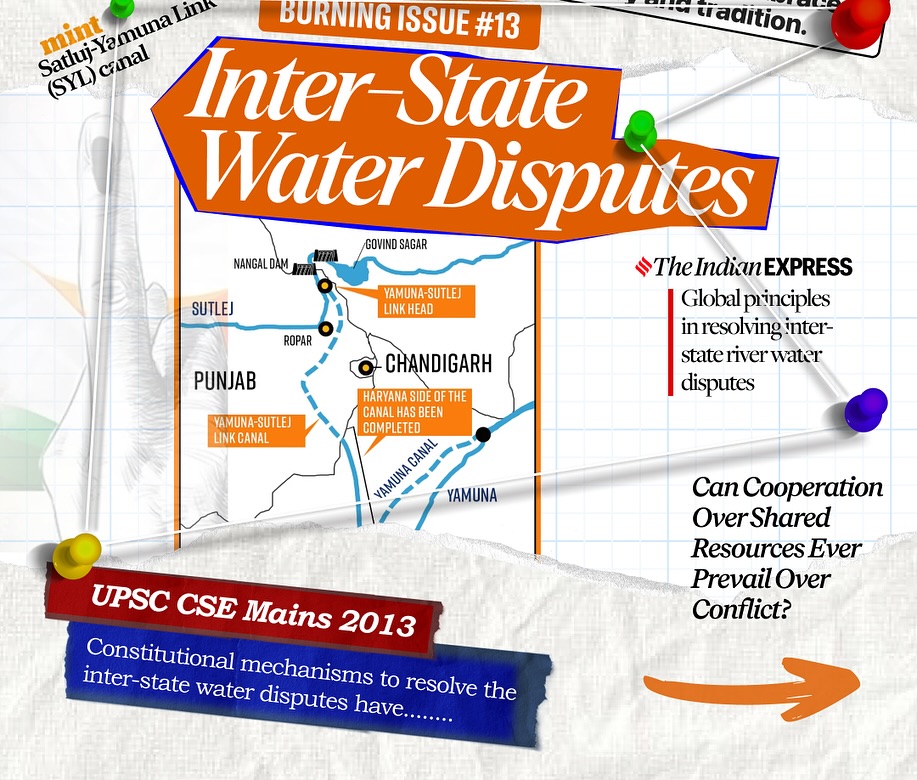

“Dip your feet in the Sutlej, and feel the cool embrace of history and tradition.” – This belief draws people to the sacred rivers of Punjab and Haryana, rivers that have nourished these lands for centuries. But while these waters have sustained generations, they are now at the heart of one of India’s most contentious water disputes.

Tensions flared after Bhakra Beas Management Board’s decision to release 4,500 extra cusecs from Bhakra to Haryana, triggering strong political and legal pushback from Punjab. As the states clash, the rivers they rely on bear the brunt.

So, how did we reach this point? Can cooperation over shared resources ever outweigh the political tug-of-war? And most critically, can we find a solution that ensures fair access to water while preserving the future of these lifelines?

About the Punjab-Haryana Water Dispute

The Punjab-Haryana water sharing dispute is not new. It has deep historical roots that go back to the very formation of Haryana as a separate state, and revolves around the complex sharing of river waters, unfinished projects, and political sensitivities that have lasted for decades.

- The dispute dates back to 1966 when Haryana was created from Punjab and was promised a share of river waters from the Ravi and Beas rivers.

- The Satluj-Yamuna Link (SYL) canal was proposed to deliver Haryana’s share but remains incomplete due to Punjab’s resistance.

- The current issue involves Punjab and Haryana over the release of additional water from the Bhakra dam, managed by the Bhakra Beas Management Board (BBMB).

- On April 30, 2025, BBMB ordered the release of 8,500 cusecs of water to Haryana for drinking needs, which Punjab opposed, claiming Haryana had already withdrawn 104% of its annual share.

- Water levels in the Bhakra, Pong, and Ranjit Sagar dams are low due to poor snowfall in the Himalayas.

- Punjab argues that BBMB’s decision is unilateral and has refused to open the Nangal dam sluice gates.

Process of Dispute Resolution

| Steps | Details |

| Legal Basis | Disputes resolved under Inter-State River Water Disputes (IRWD) Act, 1956; supported by Article 262 of the Constitution. |

| Initial Step | A state government formally complains to the Centre, stating a dispute exists or may arise. |

| Central Government Role | Examines the matter and tries to resolve it via negotiation. If it fails, a tribunal is formed. |

| Tribunal Formation | Ad hoc tribunal is set up with a chairperson (Supreme Court judge), judicial members, and technical experts. |

| Tribunal Proceedings | States present technical and legal arguments. Tribunal studies rainfall, usage patterns, crop needs, etc. |

| Timelines | Originally, no time limit. Disputes often take decades. 2019 amendment proposes stricter timelines. |

| Legal Binding Nature | Award becomes binding once notified in the Gazette by the Centre. Awards can’t be challenged in ordinary courts. |

| Enforcement Mechanism | No strict enforcement mechanisms; states delay or defy compliance due to political reasons. |

| Judicial Oversight | Though barred under Article 262, states approach SC under Articles 131 or 136 in practice. |

| Reform Proposals | 2019 Bill proposes permanent tribunal, Dispute Resolution Committee (DRC), and data agency. |

Fundamental Structural Ambiguities in resolving disputes

1. Institutional and Procedural Gaps

- Ad hoc nature of tribunals: Tribunals are formed only after disputes reach a crisis stage; there’s no permanent mechanism.

- Absence of strict timelines: Until the 2019 amendment, tribunals had no binding deadlines, leading to long delays (e.g., Cauvery tribunal took 17 years).

- No clear enforcement mechanism: Awards need central notification to become binding, and even then, enforcement remains weak.

- Overlapping forums and lack of finality: Multiple forums (tribunals, SC, Centre) operate simultaneously, with unclear jurisdictional limits.

2. Federal and Political Tensions

- Centre-state friction: States often allege the Centre’s decisions are politically influenced (e.g., Tamil Nadu vs. Karnataka).

- Perceived partiality in dispute resolution: The Centre’s dual role as a neutral arbiter and political actor creates trust deficits.

3. Legal and Constitutional Ambiguity

- Judicial overlap: Article 262 restricts SC’s role once a tribunal is set up, but states still approach courts via Articles 131 or 136, causing confusion.

- Lack of clarity on legal hierarchy: It’s unclear how tribunal awards interact with constitutional rights and Supreme Court judgments.

4. Data and Technical Challenges

- Opaque data-sharing: No standardized, independent authority to collect and verify hydrological data.

- Technical weakness: Lack of scientific modelling or agreed methodologies for calculating water sharing, flows, and drought management.

5. Absence of Preventive and Cooperative Mechanisms

- No early conflict resolution systems: There are limited platforms for dialogue or mediation before legal escalation.

- Underutilised river boards and inter-state coordination bodies: Mechanisms like river boards (per River Boards Act, 1956) have rarely been established or made effective.

6. Normative and Equity Framework Gaps

- Unclear role of equity and sustainability: No codified framework for factoring in historical use, equity among stakeholders, or ecological needs.

- Inconsistent tribunal reasoning: Different tribunals apply varying standards of equity, population needs, and usage history, lacking uniformity.

Challenges in tribunal functioning

1. Delays and Lack of Time-Bound Resolution

- Slow constitution of tribunals: The Centre often takes years to constitute a tribunal even after a dispute is formally raised by states.

- Prolonged proceedings: Tribunals frequently take over a decade to deliver awards.

- Example: The Cauvery Water Disputes Tribunal was constituted in 1990 and gave its final award only in 2007 — a gap of 17 years.

2. Non-Binding Nature and Delayed Notification of Awards

- Tribunal awards do not become binding until notified by the central government, creating room for political delay.

- Example: Cauvery award remained unimplemented for years due to notification delays and legal-political wrangling.

3. Enforcement Challenges

- No institutional mechanism for enforcement: Even after notification, compliance depends on political will and Centre’s intervention.

- States refuse compliance in politically sensitive times or if the award is seen as unfavorable.

- Example: Karnataka’s reluctance to release Cauvery waters post-tribunal award led to recurring standoffs.

4. Jurisdictional Ambiguity and Judicial Overlap

- Though Article 262 bars SC intervention once a tribunal is set up, states still approach courts under Article 131 or 136.

- This leads to parallel litigation and confusion over final authority.

- Example: Both Karnataka and Tamil Nadu moved the Supreme Court after the Cauvery award, despite an existing tribunal.

5. Lack of Uniform Standards and Precedents

- Each tribunal applies different criteria — some focus on historical usage, others on economic needs or ecological flows.

- This lack of standard methodology leads to inconsistency and perceived unfairness.

- Example: The Krishna tribunal gave weightage to catchment area and utilization, while Cauvery focused more on crop water needs.

6. Political Interference and Erosion of Trust

- Perception that tribunal processes are politically influenced, especially when the Centre delays action or notification.

- States lose faith in tribunal neutrality if the ruling party at the Centre is seen favoring a particular state.

7. Absence of Permanent Institutional Framework

- Each dispute leads to an ad hoc tribunal with fresh staffing, rules, and procedures.

- No continuity or institutional memory is maintained.

8. Technical and Data Disputes

- Lack of transparent, real-time, and credible hydrological data hampers tribunal assessment.

- States often dispute each other’s data; no independent river basin authority exists to validate claims.

- Example: In Mahanadi dispute, Odisha and Chhattisgarh had conflicting data on water usage and flow patterns.

Way Forward

- Time-Bound Tribunal Process

Amend the Inter-State River Water Disputes Act to set fixed timelines for tribunal awards and their publication in the Gazette. - Establish a Permanent Tribunal

Create a standing tribunal with multiple expert benches to handle disputes continuously and reduce delays. - Set Up River Basin Authorities

Form inter-state basin organizations for key rivers to manage planning, usage, and dispute prevention jointly. - Strengthen Centre-State Coordination

Use platforms like the Inter-State Council and NITI Aayog for political dialogue and consensus building. - Adopt Global Norms

Incorporate international principles like the Berlin Rules and Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) for fair and sustainable sharing. - Use Technology for Transparency

Deploy real-time water monitoring and forecasting systems to promote data sharing and reduce mistrust.

#BACK2BASICS: Global principles in resolving inter-state river water disputes

| Norm / Rule / Convention | Key Principle | Relevance to India |

|---|---|---|

| Helsinki Rules (1966) | Equitable and reasonable use of watercourses; Obligation not to cause appreciable harm to other states | Though non-binding, this principle supports fair sharing in Indian disputes like Krishna and Cauvery |

| UN Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses (1997) | Reinforces principles of equitable use, prior notification, and cooperation between riparian states | Reflects the need for basin-level cooperation in India’s inter-state river basins (e.g., Mahanadi) |

| Berlin Rules (2004) | Expands Helsinki Rules to include environmental sustainability, public participation, and human rights | Calls for river management in India to consider ecological flows and inclusive planning (e.g., Western Ghats rivers) |

| Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) | Promotes coordinated development and management of water, land, and related resources across sectors | Emphasizes basin-level institutions like river basin authorities, which India lacks formally |

| Principle of Prior Notification and Consultation | States must inform and consult co-basin states before undertaking major projects | Could reduce friction as seen in Polavaram (Andhra–Odisha–Telangana) and Mahanadi (Chhattisgarh–Odisha) disputes |

| No Significant Harm Principle | A state should not cause significant harm to others through its water use | Applicable to disputes involving upstream usage impacting downstream states (e.g., Yamuna, Cauvery) |

| Obligation to Cooperate | Countries (or states) must cooperate in good faith to manage shared resources | This is lacking in many Indian disputes marked by political one-upmanship |

Constitutional Provisions on Water Resources

The legal framework that governs water sharing and disputes in India is grounded in the Constitution.

- Article 262 of the Indian Constitution: This article provides a specific mechanism for the resolution of inter-state river water disputes. It empowers Parliament to enact laws to adjudicate such disputes, barring the jurisdiction of the courts. It has been the basis for the creation of the Inter-State Water Disputes Act, 1956.

- Water as a Union Subject (Article 246): Under the Constitution, water resources and their management primarily fall under the Union List (List I) of the Seventh Schedule. However, states are given jurisdiction over “water” under the Concurrent List, which leads to potential conflicts when inter-state water disputes arise.

- Inter-State Water Disputes Act, 1956: The Act provides a detailed legal framework for resolving inter-state water disputes. It stipulates that if states cannot resolve a dispute by negotiation, a Water Disputes Tribunal is to be constituted. This process is critical in managing conflicts like the one between Punjab and Haryana.

- Doctrine of Equitable Distribution: This principle, implied in Indian water law, suggests that water should be distributed fairly among states. However, the execution of this principle often faces challenges, particularly in the context of regional differences and political dynamics, as seen in the Punjab-Haryana dispute.

- The Role of Parliament: Parliament holds the authority to resolve issues of inter-state water disputes by passing legislation. For example, the Cauvery Water Disputes Tribunal was created under a Parliamentary law, although delays in such decisions have often exacerbated tensions between states.

SMASH MAINS MOCK DROP

Despite constitutional provisions and legislative mechanisms, inter-state river water disputes in India remain unresolved for decades. Analyse the structural, political, and legal factors contributing to this failure. Suggest reforms to ensure time-bound, equitable, and enforceable resolution of such disputes.”