N4S

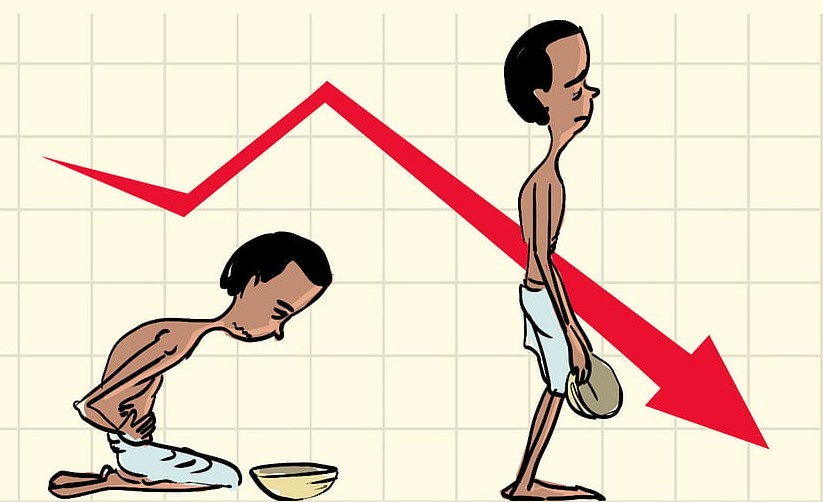

India’s poverty story is no longer about how little people earn but about how we measure, interpret, and respond to deprivation.

UPSC often asks sharp, layered questions on poverty-how it’s measured and how well welfare schemes work. The 2015 question on urban vs. rural poverty indicators is a case in point, demanding both data literacy and conceptual depth. Yet many aspirants miss key elements like PPP adjustments, demographic shifts, or the trade-offs behind India’s poverty story.

This article bridges that gap – linking older frameworks (Lakdawala, Tendulkar) with new benchmarks (World Bank’s $3/day line, MPI). Subheads like “India’s Outlier Status” and “Welfare Schemes May Need Updating” unpack why India’s poverty numbers look better—and why the full picture is more complex.

PYQ ANCHORING:

GS 2: Though there have been several different estimates of poverty in India, all indi cate reduction in poverty levels over time. Do you agree? Critically examine with reference to urban and rural poverty indicators. [2015]

MICROTHEMES: Poverty

Recently, the World Bank has announced a major revision to global poverty estimates, raising the International Poverty Line (IPL).

It raised the IPL from $2.15/day (2017 PPP) to $3.00/day (2021 PPP) (which at PPP-Exchange Rate for Indian Rupee in 2025 is Rs 20.6). Thus, it comes out to be Rs 62/day for India.

While the change led to a global increase in the count of extreme poverty by 125 million, India emerged as a statistical outlier in a positive direction. Based on this update, it is now stated that only 5.75% Indians live under extreme poverty (down from 27% in 2011-12).

About Poverty Line

A poverty line is a threshold of minimum income or consumption needed to meet basic necessities like food, shelter, and clothing.

- Purpose: It serves to identify who is poor and helps in targeting welfare schemes and tracking poverty reduction over time.

- Standards Used:

- Absolute Poverty Line: Fixed benchmark (e.g., World Bank’s $1.90/day for extreme poverty).

- Relative Poverty Line: Based on a population’s median income or living standards, reflecting social inclusion.

- Importance:

- Classifies individuals as poor or non-poor.

- Informs policy decisions, resource allocation, and efforts toward poverty alleviation.

Source – Indian Express

India’s Outlier Status in Global Poverty Reduction

| Reason | Explanation | Substantiation |

| Sustained Economic Growth | Despite COVID-19 setbacks, India has maintained a stable growth trajectory post-2015, which helped lift incomes and create jobs, especially in services and construction. | IMF estimates India’s GDP grew at 7.2% (FY23). |

| Large-Scale Welfare Schemes | Government schemes like free food (PMGKAY), LPG connections (Ujjwala), and rural jobs (MGNREGA) helped protect vulnerable groups. | PMGKAY provided free ration to ~80 crore people during COVID; MGNREGA offered 3.5 billion person-days in 2020-21. |

| Direct Benefit Transfers (DBT) | Technology-enabled transfers ensured subsidies reached the poor directly, reducing leakages and informal exclusion. | Over ₹28 lakh crore transferred through DBT since 2014 (as per govt data). |

| Declining Fertility and Demographic Shifts | Smaller family sizes mean fewer dependents and higher per capita consumption within households. | India’s Total Fertility Rate fell to 2.0 (NFHS-5). |

| Improved Access to Basic Services | Access to electricity, toilets, cooking fuel, housing, and bank accounts expanded significantly, reducing multidimensional poverty. | NITI Aayog’s MPI 2023: Multidimensional poverty halved between 2015-16 and 2019-21. |

| Revised PPP Exchange Rate | New 2021 PPP revisions increased the purchasing power of the Indian rupee, lowering the number of people under the $3.00/day threshold. | World Bank (2024): Revised PPP adjustment favoured India, unlike many African economies. |

Impact of Revision on Poverty Perception and Policy Targeting in India

1. A Higher Poverty Line Shows Deeper Poverty: The new $3.00/day line raises the basic standard for survival. It brings into focus people who were above the old line but still struggle to meet daily needs.

2. More People May Need Help: Many who were earlier not counted as poor may now be seen as poor under the new line. This means more people may need to be included in government welfare programs.

3. India’s Progress Looks Better, But Challenges Remain: India now has only about 5.75% extreme poor under the new line, which shows progress. But this average hides regional and rural-urban gaps. Many areas still have deep poverty.

4. Welfare Schemes May Need Updating: Programs like MGNREGA, free food schemes, and cash transfers may need to expand. Focus should also be on people who are not extremely poor but still vulnerable to slipping into poverty.

5. Need to Shift Toward Universal Services: The higher poverty line supports the idea that healthcare, education, and social security should be available for all, not just for the poorest.

6. India Must Update Its Own Poverty Measures: India still uses old poverty estimates. New methods, including multidimensional poverty (like NITI Aayog’s index), should be used. This helps track not just income, but also access to basic needs like education, sanitation, and housing.

Importance of the Poverty Line

- Measuring the Scale of Poverty: The poverty line provides a clear, quantifiable way to identify how many people are poor in India. This headcount is essential to understand the size of the problem and track who needs the most help.

- Monitoring Progress Over Time: It acts as a benchmark to assess whether policies and development programs are making an impact. A fall in poverty numbers over time signals improvement in living conditions.

- Targeting Welfare Schemes Effectively: Poverty line identification helps direct benefits to the right people. Many welfare schemes depend on Below Poverty Line (BPL) classification, including:

- PDS: Ration cards for subsidized grains.

- PMAY: Affordable housing in rural and urban areas.

- MGNREGA: Although universal, poverty data helps identify the most vulnerable.

- NSAP: Pensions for the elderly, widows, and disabled.

- Ayushman Bharat: Health insurance for the poorest families.

- Assessing Inclusiveness of Growth: If GDP is rising but poverty remains high, it shows that economic growth is not reaching the poor. The poverty line helps check if development is inclusive and equitable.

- Fulfilling Constitutional Goals: While the Constitution doesn’t mention a poverty line directly, the Directive Principles of State Policy require the state to create a just and equitable society. Estimating poverty supports this objective.

- Enabling Global Comparisons: Global poverty lines (like the World Bank’s $3.00/day PPP) help compare India’s performance with other countries, shaping global reputation and development policy.

Challenges with the Poverty Line in India

- ‘Basic Needs’: Defining minimum needs is subjective and evolves with time. A small change in the poverty line’s value can drastically change poverty numbers, making it politically sensitive.

- Neglect of Non-Food Essentials: Early poverty lines focused mainly on food. Later, health and education were included (e.g., Tendulkar/Rangarajan), but the assumption that the state provides these services for free often doesn’t match ground realities.

- Outdated Official Estimates: India hasn’t officially updated its poverty line since the 2011–12 Tendulkar estimates. The 2017–18 consumption survey was scrapped, and while new HCES data (2022–23) is available, poverty estimates based on it are still pending.

- Uncertainty Over Actual Trends: Economists disagree over whether poverty has truly declined as much as recent data claims. Events like COVID-19, demonetisation, and stagnant rural wages suggest setbacks for the poor that may not reflect in outdated estimates.

- Regional Variations: One uniform poverty line fails to reflect differences in living costs and service access across states or between rural and urban areas. A national line may oversimplify complex regional realities.

Way forward

1. Mandate for a Modern Basket: The government should immediately constitute a new expert committee, similar to the Tendulkar and Rangarajan committees, but with a broader and more contemporary mandate. This committee should define a “Poverty Line Basket” (PLB) that truly reflects the minimum requirements for a dignified life in 21st-century India. The committee should recommend a mechanism for periodic revision and updating of the poverty line (e.g., every 3-5 years) to account for inflation, changes in consumption patterns, and evolving societal standards.

2. Leverage the Latest HCES Data (2022-23): The HCES data should be fully utilized to derive poverty lines and estimates at state-specific, rural-urban, and potentially even sub-state levels, reflecting the vast economic and cost-of-living disparities across India.

3. Embrace a Multi-Tiered Approach to Poverty Measurement: India should move beyond the debate of a single poverty line. A multi-tiered framework would be more appropriate:

- Extreme Poverty Line: Aligned with the World Bank’s international poverty lines (e.g., the revised $3.00/day PPP) for international comparisons and to track progress on SDG 1.

- National Poverty Line: A domestically derived, consumption-based line reflecting the minimum for a dignified life. This could be akin to a “basic needs” poverty line.

- Vulnerability Line/Near-Poor Line: A line slightly above the national poverty line to identify households that are not officially “poor” but are highly vulnerable to falling into poverty due to economic shocks (e.g., illness, job loss, climate events). This group also needs policy attention.

4. Strengthen Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI): The MPI should be officially recognized as a primary and complementary tool for poverty measurement, not a replacement for a consumption-based line. Use MPI to identify specific deprivations (e.g., sanitation, cooking fuel, education access) at granular levels (district, block) to design targeted, multi-sectoral interventions. Continuously improve the data sources and frequency for MPI calculation (e.g., by integrating HCES data with NFHS and other administrative data).

#BACK2BASICS: Tracking India’s Poverty

Various Approaches to Tracking Poverty

India and the world have used different methods to track poverty. Each method has strengths and limitations.

1. Consumption-based Poverty

- What it is: Tracks how much people spend on food, housing, clothes, etc.

- Used by: India’s official poverty estimates (like Tendulkar Committee, 2011-12).

- Pros:

- Better reflects long-term wellbeing, especially in informal economies like India’s.

- More stable and less affected by income shocks.

- Cons:

- Requires detailed surveys, often delayed.

- May underestimate urban poverty and non-food needs.

2. Income-based Poverty

- What it is: Based on how much a person earns, usually per day or per month.

- Used by: World Bank’s International Poverty Line ($2.15 or $3/day).

- Pros:

- Easy global comparison.

- Can reflect short-term changes in wellbeing.

- Cons:

- Inaccurate in informal sectors where incomes are irregular or underreported.

- May miss consumption from savings, credit, or in-kind transfers.

3. Multidimensional Poverty

- What it is: Looks at poverty beyond income—includes access to education, health, sanitation, housing, and nutrition.

- Used by: NITI Aayog’s MPI, UNDP’s Global MPI.

- Pros:

- Holistic. Shows how poor people are deprived in multiple areas.

- Helps target specific policies (e.g. education in Bihar, sanitation in UP).

- Cons:

- Complex to calculate.

- Needs regular, high-quality data.

| Alagh Committee (1979) | Developed the poverty lines for rural and urban areas based on nutritional requirements (2400 kcal for rural, 2100 kcal for urban). These calorie norms were subsequently accepted by the Planning Commission. |

| Lakdawala Committee (1993) | Recommended using Consumer Price Index for Agricultural Labourers (CPI-AL) for rural areas and Consumer Price Index for Industrial Workers (CPI-IW) for urban areas to update state-specific poverty lines. It emphasized that poverty estimates should be based on consumption expenditure surveys conducted by the National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO). |

| Tendulkar Committee (2009) | It moved away from a solely calorie-based model and recommended a more comprehensive “Poverty Line Basket” that included private expenditure on health and education, in addition to food and other basic necessities. It also recommended a uniform poverty line basket across rural and urban areas, though with different monetary values. Based on its methodology, the Tendulkar Committee estimated the poverty line for 2011-12 at:₹816 per capita per month for rural areas (~₹27.2 per day)₹1,000 per capita per month for urban areas (~₹33.3 per day)Using this line, India’s poverty rate was estimated at 21.9% (25.7% rural, 13.7% urban), meaning approximately 26.93 crore people were below the poverty line. |

| Rangarajan Committee (2014) | Constituted to review the Tendulkar methodology, this committee proposed higher poverty lines, considering a slightly different consumption basket. Poverty Line:₹972 per capita per month for rural areas (~₹32.4 per day)₹1,407 per capita per month for urban areas (~₹46.9 per day)Based on these lines, the Rangarajan Committee estimated India’s poverty rate to be 29.5% for 2011-12, significantly higher than the Tendulkar Committee’s estimate. However, the Indian government did not officially adopt the Rangarajan Committee’s recommendations, meaning the Tendulkar Committee’s estimates (for 2011-12) remained the last official poverty figures for a long time. |

| World Bank | The World Bank’s current extreme poverty line is $2.15 per day (2017 PPP). Recently, the World Bank announced a revision to $3.00 per day (2021 PPP). At the 2025 PPP rate, this translates to roughly ₹62 per day for India. Using the World Bank’s updated line, about 5.75% of Indians live in extreme poverty as of 2025, a sharp decline from 27% in 2011–12. |

| NITI Aayog | National Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI): Unlike a purely income/consumption-based poverty line, the MPI measures poverty across multiple dimensions (health, education, and living standards) using 12 indicators (e.g., nutrition, schooling, cooking fuel, sanitation, electricity, housing, assets, bank accounts). NITI Aayog’s recent reports (based on NFHS data) show a significant reduction in multidimensional poverty in India:From 29.17% in 2013-14 to 11.28% in 2022-23, with approximately 24.82 crore people escaping multidimensional poverty in 9 years.Rural poverty showed a larger decline than urban poverty in this period.This provides a more holistic picture of deprivation beyond just monetary income. |

SMASH MAINS MOCK DROP

While India has shown remarkable reduction in poverty as per global estimates, the outdated nature of domestic poverty lines hampers effective policy targeting.” Critically examine in light of recent revisions in the international poverty line and India’s welfare architecture.